Experiences of Japanese Americans under the AEA

Minoru Nakano and the Weight of “Enemy Alien”

On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and fear and anger directed towards Japanese Americans worsened. Once President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, it was at an all-time high—and the Japanese immigrants knew it. Desperate to prove their American identity, they hid their Japanese culture – but those born in Japan were classified as enemy aliens.

Which brings up the question: Does it really matter what you do or say if you will always be seen as an “enemy alien”?

For Minoru Nakano, a successful general contractor in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, this shift was immediate and devastating. Despite decades of building homes, schools, and community institutions, despite being a father and husband with no meaningful connection to the Japanese military or government, he was detained by the U.S. government under martial law. Transferred to the U.S. and held under the Alien Enemies Act, he was denied a charge, a trial, and the U.S. had no true evidence of wrongdoing.

From Fukuoka to Honolulu

Born in Kurume-shi, Fukuoka, Japan, Minoru had moved to Hawaiʻi in 1915. There, he found opportunity. He started a contracting business, built homes for plantation workers, and became a leader in several Japanese community organizations. He was known, respected, and active in public life

But when war broke out, that visibility became a liability.

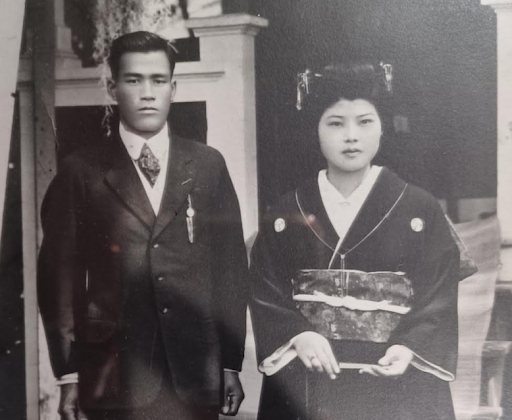

Pictured: Minoru and his wife, Sugano Nakano

Pictured: Nakano Family in Hawaiʻi. Minoru is on the far left

After the U.S. declared martial law in Hawaiʻi, the FBI came to the Nakano household. They searched for evidence of disloyalty and found none. Nevertheless, Minoru was detained. His wife and children could only watch as he was taken away, with no knowing where or why.

At a military hearing, Minoru expressed opposition to Japan’s aggression in the Pacific. He made clear he had no interest in returning to Japan and planned to live in Hawaiʻi until the end of his life. But his words didn’t matter. The tribunal decided he posed a potential risk—that he was “pro-Japanese.” He was initially detained at the Sand Island internment camp and then shipped to the mainland United States and held in internment camps at Angel Island, Fort Sam Houston, Lordsburg, and Santa Fe.

Pictured: Jerome, Arkansas WRA camp. Second from the right is Bert Nakano; next to him is his older brother, Jitsuo Nakano. Their younger brother James is behind them in the middle—all others were friends.

“No-No” and the Loyalty Questions

Meanwhile, Minoru’s family was uprooted. They were forced to leave Hawaiʻi with 1,500 other Japanese Hawaiians, transported across the ocean and sent to Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas. Eventually, Minoru was paroled to join them.

There, all Japanese Americans over the age of 17 were issued a “loyalty questionnaire.” Most questions were routine—but two stood out:

Question 27: Are you willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces wherever ordered?

Question 28: Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear allegiance to the Japanese Emperor?

Answering “no” to both questions—especially without U.S. citizenship—was not necessarily an act of disloyalty. For many Issei like Minoru, swearing allegiance to the U.S. could leave them stateless. And for those already imprisoned without due process, being asked to serve the very country that incarcerated them felt deeply unjust.

Minoru and his eldest son, Jitsuo, both answered “no” to Questions 27 and 28. They were labeled “No-No Boys” and sent to Tule Lake.

Tule Lake: Protest or Patriotism?

At Tule Lake, groups known as the Hoshidan and Seinen-dan rose to prominence. They organized protests, marched in military-style formations, and openly expressed outrage at U.S. government treatment. Some believed in Japan’s imperial cause, but for many others, the Hoshidan and Seinen-dan became vehicles for expressing trauma, rage, and grief.

Fires broke out in the camp. Most suspected arson, likely tied to Hoshidan/Seinen-dan protest. Minoru and Jitsuo were accused—rightly or wrongly—of affiliating respectively with the Hoshidan and Seinen-dan. They were arrested and returned to Santa Fe.

That left Sugano Nakano, Minoru’s wife, to care for the family alone in Tule Lake. Their teenage son Bert became the main caretaker for his ailing mother, younger brother, and newborn sister, Akemi. The burden was immense. Bert recalled moments of comedy—like trying to make a week’s worth of milk for Akemi, only to be scolded after it spoiled—but those few laughs were overshadowed by the slow unraveling of his family.

Sugano’s health declined rapidly. The stress of displacement, the shame of incarceration, and the absence of her husband took a visible toll. Her hair grayed prematurely. Her energy faded, and though Bert did his best, he was still just a child.

After the War: Loss and Survival

Minoru was released on December 3, 1945, and was briefly sent to Los Angeles. On December 4, he and his family returned to Hawaiʻi. But home was not what it once was.

His business was gone. His reputation had been erased. The life he had built through decades of work had been dismantled in a matter of weeks.

Within a year, Sugano passed away from a stroke—her body giving in to the trauma she could no longer hold. Minoru remarried twice, but never recovered emotionally or professionally from the internment. He became an alcoholic and eventually returned to Japan. He died of a stroke at the age of 62.

Picture: An NCRR banner held up just outside of the redress hearings 1981. Courtesy of the Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress Archives Collection. The photo can be found in Densho Digital Archives.

Legacy and Redress

Bert Nakano carried the weight of his father’s history with him. After relocating to Chicago with his wife, Lillian, and later to Los Angeles, he became deeply involved in civil rights activism. Highly encouraged by his son Erich, Bert joined the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO), which fought the displacement of Japanese American residents and small businesses.

Out of that grassroots activism emerged something larger: the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations (NCRR). Bert became the organization’s spokesperson with Lillian, a behind-the-scenes leader and speechwriter. Together, they helped transform community trauma into organized political action, and mobilized many Nikkei to fight for redress and reparations.

The NCRR played an impactful role in mobilizing Japanese Americans to testify at hearings held by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). Survivors, many speaking publicly for the first time since the war, told stories of incarceration, loss, and lasting psychological scars.

Final Thoughts

Thanks in part to the efforts of Japanese Americans such as Bert Nakano, the NCRR, and many Japanese American groups, in 1988, the U.S. government passed the Civil Liberties Act, granting a formal apology and monetary reparations of $20,000 to over 60,000 survivors.

But for Bert Nakano, redress could never undo what had happened.

“To people who would oppose reparations, I’d say: ‘Give me back my three years, my mother’s health, my father’s business, my brother’s ambition to become a doctor—and they can keep their money.’”

The redress was a victory—but it came too late for many. The trauma, the loss, the years behind barbed wire—all rooted in a government decision to see its own people not as citizens, but as threats. It proved that what they did and said mattered, that they had the right to be seen, not as “enemy aliens,” but as Americans.

While redress could never undo the damage, and it came too late for many. Erich Nakano remembers, “I—and I think my parents—felt it was still momentous and deeply cathartic for the community. It was a milestone in the long struggle for civil rights.”

The movement itself was transformative. Through testimony at the CWRIC hearings, rallies, Days of Remembrance, and lobbying, Japanese Americans turned pain into action and shame into pride. For the first time, many Issei and especially Nisei shared their stories publicly, shifting the blame from themselves to where it belonged—the U.S. government. That sense of helplessness was replaced with the belief that we could stand up, fight, and be heard.

Its impact still resonates today in the renewed pride of younger generations, and in the responsibility we feel to stand with others facing injustice—whether Muslims after 9/11 or immigrants today. It was never just about the money, but about a movement that reshaped our community, culminating in the 1988 Civil Liberties Act.

Written by: Kiyone Tanaka-Gacayan, based on original documents and interviews with Erich Nakano, grandson of Minoru Nakano.

References:

Want to hear about more experiences of others under the AEA? Click a name below to learn more.