Experiences of Japanese Americans under the AEA

Kahei Sam Morikawa

Kahei Sam Morikawa, born on January 5, 1879, in Yamaguchi, Japan, is remembered not only as a husband, father, and community leader but also as a symbol of strength and resilience in the face of state-sanctioned injustice. He married Tsuta Nakashima in 1907, and together they raised seven American-born children. One of their daughters, Itsue Morikawa Nakatsuka, would later connect to the lineage of Katie Masano Hill through her marriage to Keiji Nakatsuka—Katie’s great-grandfather Mitsuo Nakatsuka’s brother—making Kahei a deeply significant figure in Katie’s family history.

Kahei immigrated to the United States with Tsuta in 1909. They settled in Tacoma, Washington, where he lived for 33 years before the outbreak of World War II. During that time, Kahei became an established member of the Japanese American community and was recognized for his leadership as head of the Japanese Grocers Association. He raised his family in a manner that emphasized loyalty to the United States, encouraged civic participation, and built strong, trusting relationships with non-Japanese neighbors.

Kahei’s Alien Enemy Docket Internee Card

However, like many Japanese immigrants labeled “enemy aliens,” Kahei's decades of peaceful life and contribution to society were abruptly disregarded following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. At 63 years old, Kahei was arrested under the Alien Enemies Act on February 2, 1942, in Seattle, Washington. He was not given any notice, and was not given the opportunity to consult an attorney when the FBI showed up and took him to the Seattle INS Detention Station, beginning a long and painful odyssey through a series of incarceration sites without ever learning what the charges were against him.

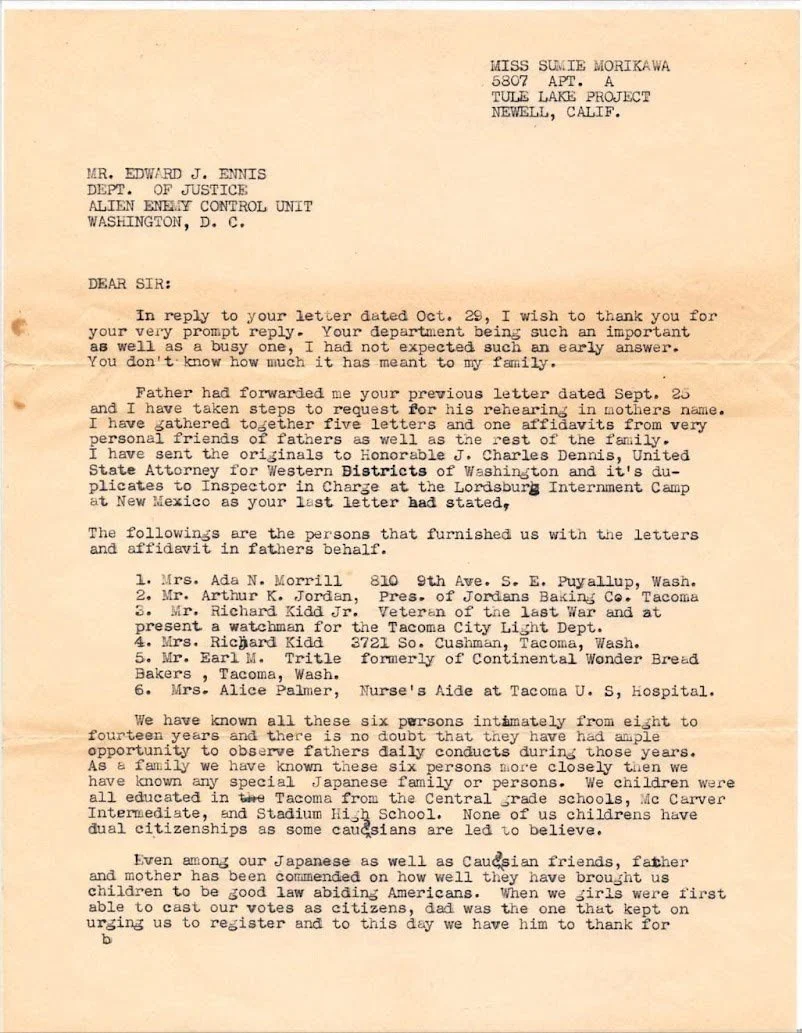

In her October 29, 1942 letter to the Department of Justice, Sumie passionately defended her father's character and their family’s loyalty. She listed testimonials from six respected non-Japanese community members—neighbors, employers, veterans—who vouched for Kahei’s conduct and patriotism. She recounted how he encouraged his daughters to vote and supported war bond purchases even before the war, showing deep civic commitment.

Sumie’s letter also described how the family continued Kahei’s work in supporting the U.S. war effort, even after he was taken away. Despite selling his store under duress just before evacuation, they used the remaining funds to invest in war bonds in her sister’s name—an act of deep patriotism during a time when their country labeled them enemies.

Notes from DOJ Workers on Kahei’s AEA Internee Card

His journey continued with a formal warrant issued on March 8, 1942. On March 20, he was transferred to Fort Missoula, Montana, a Department of Justice internment camp where many Japanese “enemy aliens” were interrogated and detained. On August 27, 1942, he was sent to Lordsburg, New Mexico, then to Santa Fe Internment Camp on June 14, 1943. Despite being deemed parole-eligible, the process was excruciatingly slow. He was sent to Tule Lake Segregation Center in California on July 20, 1943, and then to Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah on September 27, 1943, making it his sixth site of imprisonment. He was never given the opportunity for a judicial hearing to prove his innocence.

Throughout his internment, his daughter Sumie Morikawa advocated tirelessly for his release. Her letters provide a powerful and personal window into the emotional toll the incarceration inflicted on the family—and how unjust and disheartening the system was, even to loyal families.

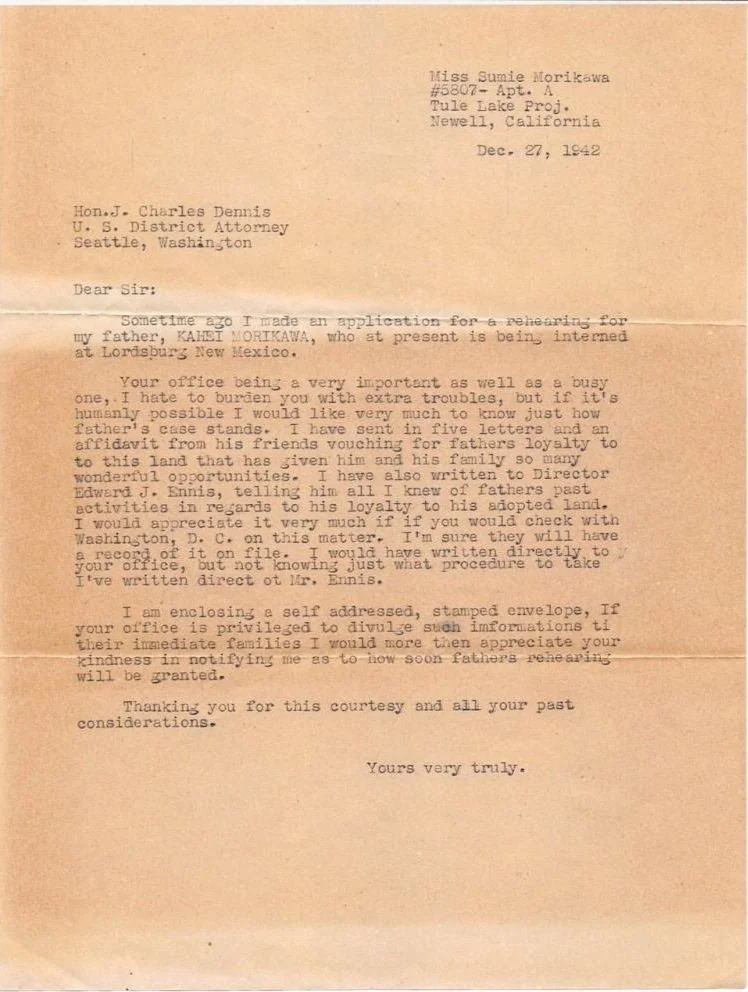

In a December 27, 1942 letter to U.S. Attorney J. Charles Dennis, Sumie followed up on Kahei’s case, pleading for an update on his parole status. She enclosed a self-addressed, stamped envelope, quietly emphasizing how little power she had in a process controlled by opaque bureaucracy. Her tone was respectful, yet full of emotional urgency.

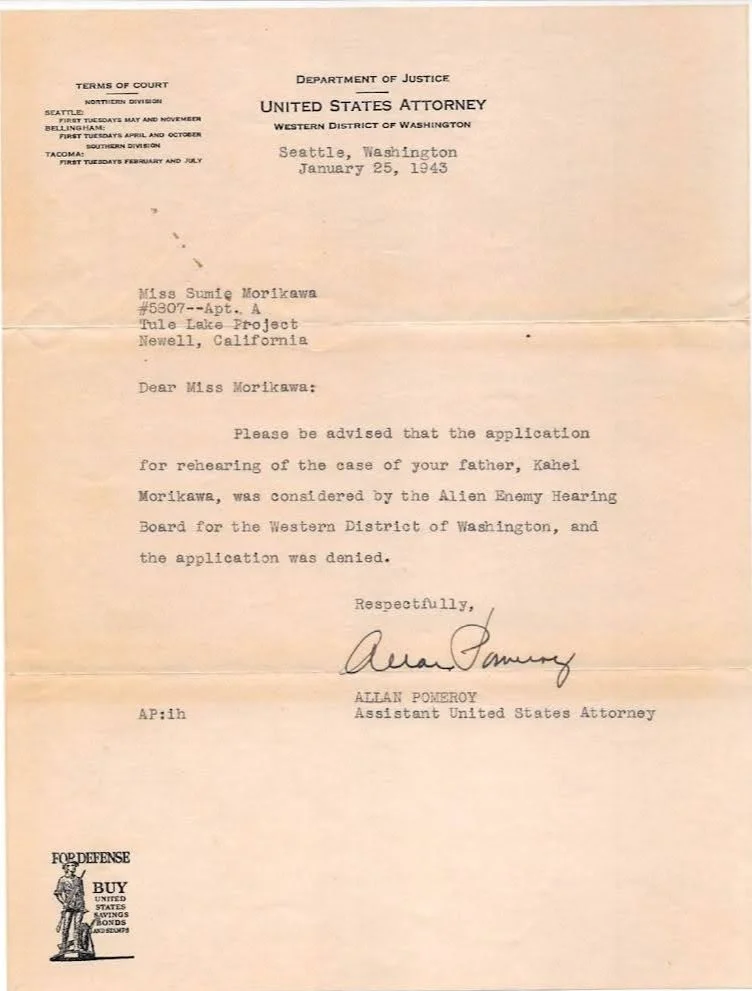

The response came on January 25, 1943, with a curt denial from Assistant U.S. Attorney Allan Pomeroy. Despite the family’s appeals, the Alien Enemy Hearing Board rejected Kahei’s application for rehearing. This cold, bureaucratic dismissal starkly contrasts with the warmth and humanity expressed in Sumie’s letters.

Still, Sumie pressed on. In a July 5, 1943 letter to Director Edward Ennis of the Enemy Control Unit in Washington D.C., she acknowledged a prior communication regarding her father's potential transfer to a WRA center. She politely pressed for information on when her father could be paroled and reunited with the family. Even as the war dragged on and other internees were being relocated, Kahei remained separated from his loved ones, with no clear answer.

Sumie’s advocacy, courage, and heartbreak speak volumes not only about the injustice inflicted on her father, but also about the unwavering strength of Japanese American families during one of the darkest chapters in U.S. civil rights history. Her words offer more than testimony—they serve as a preservation of dignity in a time of indignity.

Kahei Sam Morikawa’s story echoes that of countless Issei who built lives in America, only to be criminalized for their ancestry. Yet, what makes his story especially poignant is the way his children responded—with loyalty, with action, and with love. His incarceration, the indignities he endured, and the efforts his family made on his behalf are part of the broader tapestry of Japanese American perseverance.

For descendants like Katie Masano Hill, this history is more than inherited trauma—it is a responsibility and a calling. To remember Kahei is to affirm that he was not an “enemy alien,” but a father, community member, and American in every meaningful sense. His legacy endures through the voices of his descendants who ensure his story is not forgotten.

Kahei passed away on October 26th, 1975, in Rocky River, Ohio, when he was 96 years old.

Written by Katie Masano Hill, Kahei’s great-grand niece

Want to hear about more experiences of others under the AEA? Click a name below to learn more.