Experiences of Japanese Americans under the AEA

Heigoro Endo

My grandfather, Heigoro Endo, came to the U.S. from Shizuoka-ken in 1900. He was 14 1/2 years old. He had jobs as a railroad and farm laborer, store owner, and tuna fisherman at Terminal Island before opening a sportfishing business in San Pedro. Heigoro was a member of several organizations, including the Shizuoka prefectural association and a Los Angeles Buddhist temple. He was president of an organization of Shizuoka fishermen and a board member of the Compton Gakuen, a prominent Japanese language school. On the eve of World War II, Heigoro and his family moved into a newly constructed home. He intended to live the rest of his life in the U.S.

On March 30, 1942, individuals of Japanese descent in the Los Angeles Harbor area, including the Endo family, were given seven days to prepare to leave their homes for the Santa Anita detention center. This was part of the removal of West Coast Japanese under Executive Order 9066. However, two days later, the FBI arrested my grandfather under the authorization of the Alien Enemies Act.

In this time of great crisis, Heigoro’s family had to prepare for their move without him. They were forced to quickly dispose of personal and business possessions, which led to substantial financial losses. For example, his family was only able to sell a fishing boat and two barges for seven percent of their true value. The family lost about $850,000 in today’s currency.

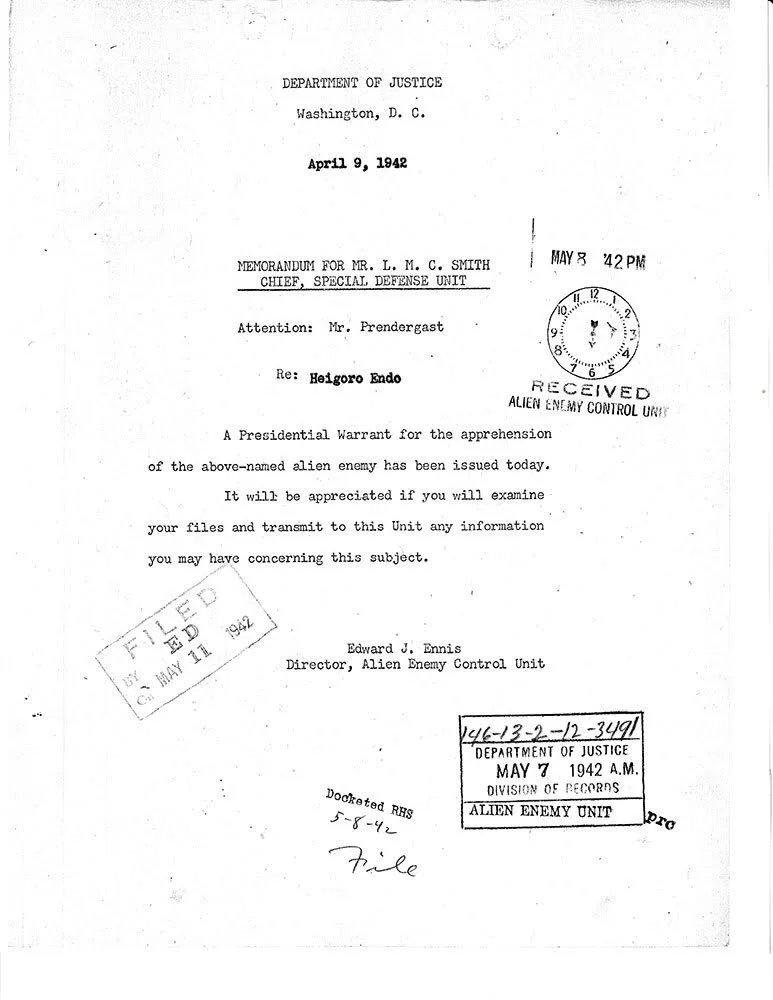

When the FBI arrested my grandfather, they did not have the requisite Presidential Warrant, which was issued eight days later and back-dated. He was part of a mass arrest of several hundred Japanese language school personnel in Southern California. A warrantless search of his home was conducted. Without explanation, he was sent to the Department of Justice’s Tuna Canyon Detention Station.

Like all detained enemy aliens, Heigoro was given a hearing. My father was able to attend, and his later recollections bring to mind the colloquial phrase “kangaroo court.” It seems clear that the purpose of the hearing was to justify my grandfather’s arrest and confinement. Accusations were made which were presumed to be true, and it was up to him to refute these. He was not allowed to have legal counsel.

Written material introduced at the hearing included seven affidavits and six personal letters from friends and business associates attesting to Heigoro’s high moral character, good reputation, and loyalty to the U.S. These were never discussed. What was discussed was his FBI arrest report.

In response to allegations, my grandfather denied that his language school was promoting allegiance to Imperial Japan. He was involved because he wanted the American-born Nisei to be able to better communicate with their Issei parents. Heigoro denied other absurd accusations such as monitoring of U.S. Navy activity and giving secret information to Imperial Japanese submarines. At one point, the FBI lied about finding contraband (hunting guns, binoculars, and a camera) in Heigoro’s home at the time of his arrest. He had actually turned these in earlier to the San Pedro police, and he had receipts to prove this. It was because of this embarrassing turn of events for the government that I believe Heigoro was paroled to rejoin his family at Santa Anita rather than being permanently interned at an Army camp.

Beyond violating my grandfather’s rights, this experience had other consequences. Some people wondered why was he arrested by the FBI if he was innocent; this stigma affected his social relationships. Under the 1948 Evacuation Claims Act, Heigoro filed a claim for his wartime losses. Years later, only two-thirds of the dollar amount was approved. An attorney’s letter suggests that one government concern was his 1942 arrest and detention.

After the war Heigoro, like many Issei imprisoned under the AEA and/or EO9066, was too old to regain his former economic status. He was an apartment manager for several years and then retired. My grandfather never spoke with bitterness about his experiences but he felt the pain of being separated from his family and the injustice of being arrested and detained. My father felt this affected Heigoro’s mental outlook and that he became a less vibrant, more reserved, and less optimistic person. My grandfather became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1955.

Written by: Russell Endo, Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies at the University of Colorado (retired)

Want to hear about more experiences of others under the AEA? Click a name below to learn more.