Experiences of Japanese Americans under the AEA

Masuo Yasui - The Legacy of the Father Behind Min Yasui's Fight for Constitutional Rights

Our grandfather, Masuo Yasui, was born on November 1, 1886, in the village of Nanukaichi in Okayama Prefecture, Japan. He left Japan at the age of sixteen alone, with little more than ambition and the hope for opportunity in America. Like so many immigrants, he believed in working hard, building a future, and giving back.

Masuo arrived in Seattle in 1903 and soon joined his older brother in Montana, working as a laborer for the Oregon Short Line Railroad. He spent his earliest years in the U.S. working difficult, low-paying jobs, often outdoors and under dangerous conditions. Despite the grueling labor, he didn’t allow the language barrier or discrimination to define him. When he moved to Portland in 1905, he worked as a houseboy while studying English at night and converting to Christianity. He achieved fluency within two years—something that would prove essential in the years to come as he became an interpreter, mediator, and advocate for others in the Japanese community who struggled to navigate American systems.

Portrait of Masuo Yasui. Courtesy of Densho, The Yasui Family Collection

He opened the Yasui Brothers Store in Hood River, Oregon, in 1908. That store, co-founded with his brother Renichi Fujimoto, was more than a business—it was a community gathering place. They sold goods, offered services, and helped local Japanese laborers find seasonal work. The store became a central hub for Hood River’s growing Nikkei community, especially as more Issei farmers came to the area to farm. In 1912, Masuo proposed by letter to a young woman he had known back in Japan, Shidzuyo Miyake. She accepted and immigrated to the U.S., marrying Masuo upon arrival. She was educated, a high school teacher, intelligent and strong-willed. Together they raised nine children—seven of whom survived into adulthood—including Minoru Yasui, who would go on to become a civil rights icon.

Masuo couldn’t own land due to Oregon’s alien land laws, so he found creative ways to help other Issei lease or buy land for farming. He became active in civic life—helping to found the Japanese Community Hall, serving as a board member for the Apple Growers Association, and even participating in the local Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club. In 1931, he became the first Japanese member of the Hood River Rotary and the first Japanese director of the fruit growers’ cooperative. Despite being denied the opportunity to apply for U.S. citizenship due to long-standing, racially-discriminatory laws, he was committed to the American ideals of democracy and equal rights.

Masuo Yasui and Family, Circa 1920s. Courtesy of Densho, The Yasui Family Collection

Masuo Yasui recieving the Silver Loving Cup award, presented by the Hood River Japanese community in appreciation for services rendered. Hood River, Oregon, c. 1935. Courtesy of Densho, The Yasui Family Collection

After Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese, the U.S. government viewed Japanese immigrants—even those who had lived peaceful, productive lives for decades—as suspect. Five days after the attack, the FBI came to arrest Masuo. The evidence they used against him was heartbreaking in its absurdity. Government officials confiscated a map of the Panama Canal that they found when they searched his home. It had been drawn by one of his children as a school project, but the official questioning him demanded he prove that he hadn't planned to blow up the Canal. Even more suspicious to the FBI was an award given to him by the Japanese government in recognition of his service to other Japanese immigrants. Masuo's role as an advisor and leader of his community was proof enough that he was a "potentially dangerous" enemy alien.

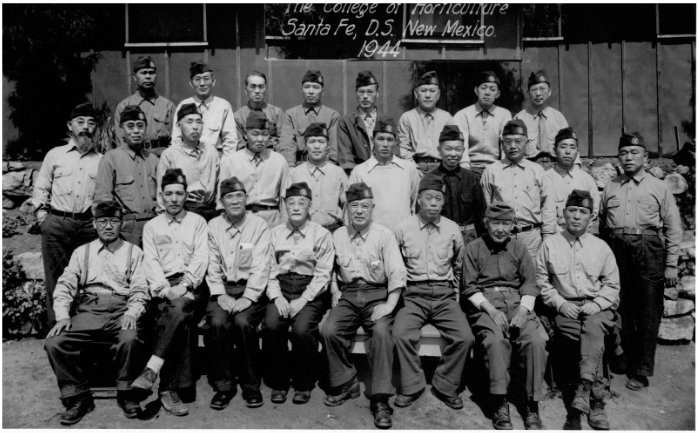

He was taken from his family and cycled through a series of Department of Justice camps across the country: first the Multnomah County Jail, then Fort Missoula in Montana, Fort Sill in Oklahoma, Camp Livingston in Louisiana,and finally, he was incarcerated along with other Japanese community leaders - teachers, ministers, civic mentors - in a camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico.He was never provided legal representation, he was never charged with a crime. Instead, he spent years as a government prisoner; his freedom taken from him solely because of his ancestry.

Meanwhile, our grandmother was incarcerated at Tule Lake camp in Northern California. She was later granted leave to join family who had been released to work the sugar beet fields in Montana. Masuo was released in January, 1946, five months after the war ended, and joined Shidzuyo in Denver, where she had settled with other family.

Courtesy of Densho, The Yasui Family Collection

Even after his release, life in Hood River was no longer safe. Our grandfather, who had once helped build that community, was told that his family was no longer welcome there. The Hood River News ran full page ads listing the properties still owned by Japanese farmers by name, and warned them to sell out and stay away.

Masuo and Shidzuyo relocated to Portland to start over. After 38 years of painstakingly building their farming and retail businesses, they had lost their store and all but one of their many fruit farms. Throughout the war, their assets had been frozen by the government but their properties continued to be taxed, and their savings were largely wiped out. In 1952, they finally gained citizenship when the McCarran-Walter Act removed racial barriers to naturalization. Masuo used his English and legal knowledge to help other Issei apply for citizenship as well. But the wounds of betrayal ran deep. According to our family, our grandfather never truly recovered from the loss of dignity, trust, and community he had once known. He grew anxious and fearful that the FBI was coming once again to arrest him.

On May 11, 1957, Masuo died by suicide. He is buried in Idlewilde Cemetery in Hood River, the town that both welcomed and rejected him. He was 70 years old.

Yet his legacy didn’t end there. Believing that education was an asset that no one could ever take away, Masuo and Shidzuyo managed to send all of their children to college. Their son, Minoru Yasui, became the first Japanese American to graduate from the University of Oregon law school and to be admitted to the Oregon bar. In 1942, Min challenged the constitutionality of wartime curfew orders imposed on people of Japanese descent and took his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

To the end of his life, Min never gave up trying to get the Supreme Court to revisit his WWII conviction. He believed deeply that unless the Court was made to confront the constitutionality of the Alien Enemies Act, there would always be a risk that the government could again single out people based on race or ethnicity for incarceration or other restrictions during wartime.

He was right—and we’re now seeing the consequences of that unresolved issue. We also know he would be disheartened to see today’s Court so reluctant to place limits on executive power, potentially ignoring the very constitutional concerns he fought so hard to raise.

In 2015, Min was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama who said, “Min never stopped believing in the promise of his country ... never stopped fighting for equality and justice ... Min’s legacy has never been more important. It is a call to our national conscience; a reminder of our enduring obligation to be “the land of the free and the home of the brave”.

It was one of the highest civilian honors in the United States—an acknowledgment not just of Min’s commitment to safeguard the principles of the Constitution, but also our grandparents' faith in the American dream.

Edited by Lise and Barbara Yasui, granddaughters of Masuo & Shidzuyo Yasui

Densho Encyclopedia, “Masuo Yasui,” Densho Digital Repository. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Masuo_Yasui/

Want to hear about more experiences of others under the AEA? Click a name below to learn more.