Experiences of Japanese Americans under the AEA

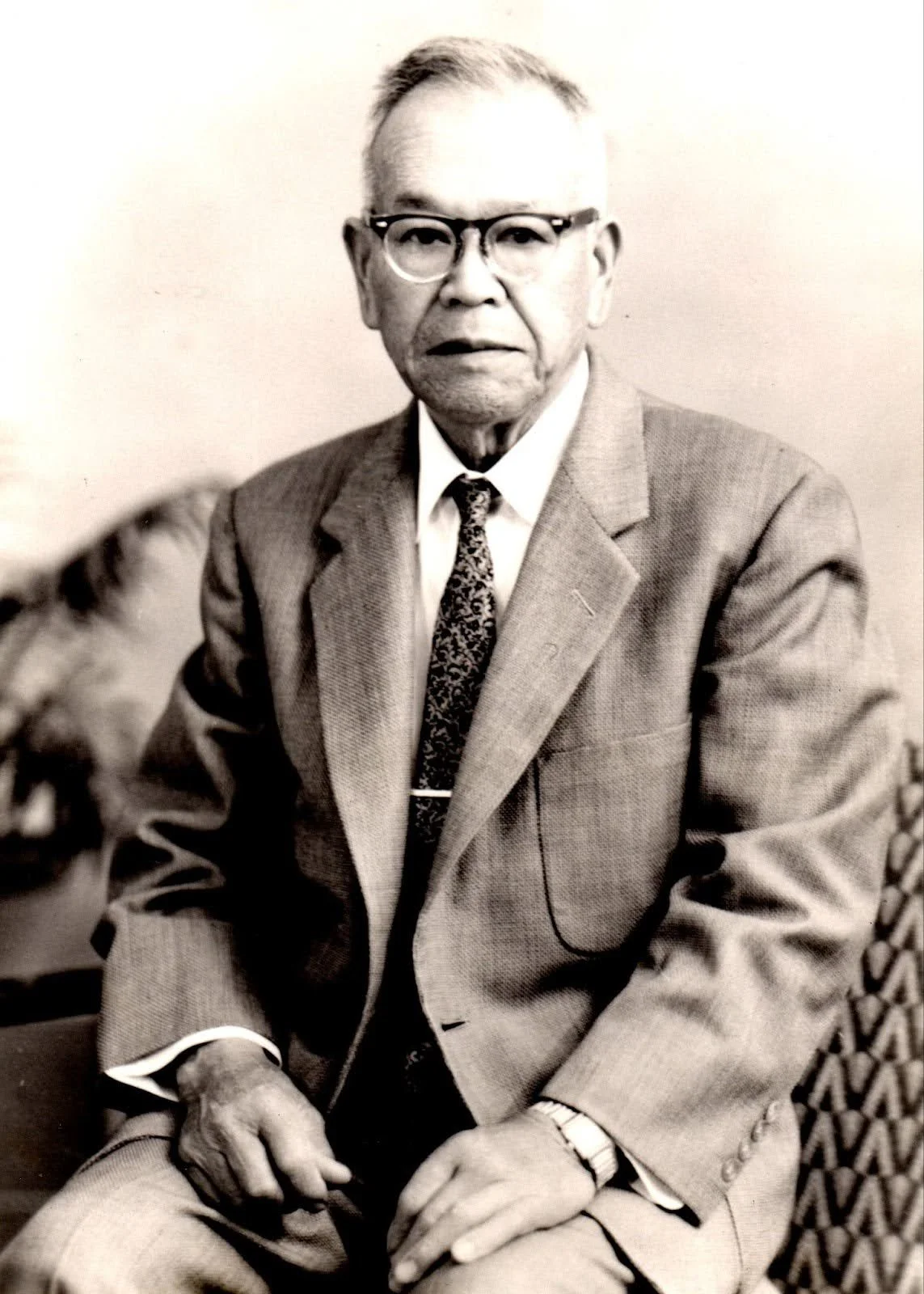

Kunitomo Mayeda

Kunitomo Mayeda was 51 years old when he was arrested by the FBI on March 19, 1942. He received no prior notice, no charges, and was taken while his teenage son was at school. A few weeks after Pearl Harbor, the FBI had come to question Mr. Mayeda and ransacked the house. Despite signing a loyalty pledge to the United States shortly after Pearl Harbor—and despite his eldest son enlisting in the U.S. Army—Mr. Mayeda was held as an “enemy alien,” transferred through a series of detention centers including Tuna Canyon and ultimately confined in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was never charged with espionage or sabotage. His hearing, held without counsel and with no family member present, functioned more as a justification for his imprisonment than a true review of facts. As Professor Russell Endo later concluded, the process presumed guilt, not innocence. Mr. Mayeda remained imprisoned for the entire duration of WWII, over three years, from March 19, 1942, until some time in 1945.

Mr. Mayeda came to the United States in 1907 as a 16-year-old boy with dreams of studying English and serving as a diplomat to bridge Japanese and American cultures. He devoted his life to building a future in his adopted home, and worked as a houseboy and chef—once at the prestigious Hotel del Coronado—before turning to farming. On leased land in San Diego (as Japanese immigrants were barred from owning property), he cleared fields, dug irrigation ditches, built roads and a home, and cultivated crops like celery and tomatoes. This backbreaking labor established roots not only for his family but for a growing Japanese American community.

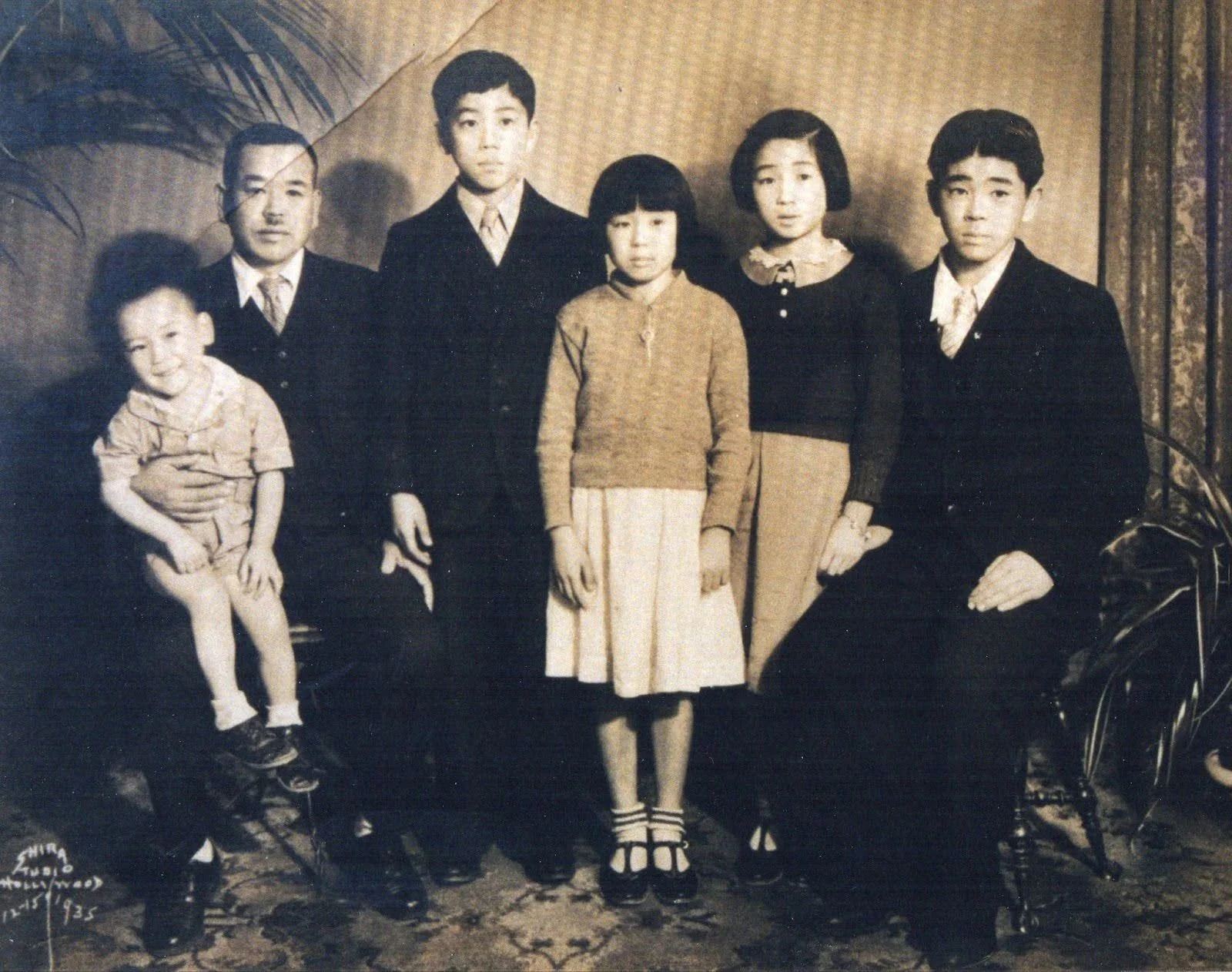

Kunitomo Mayeda and Family Circa 1935

By the 1930s, Mr. Mayeda had five children, all born in the United States. After his wife passed away in the mid-1930s, he returned to Japan to remarry and raise the youngest children there. However, Mr. Mayeda’s two oldest sons attended high school in the San Diego area and thrived there: son Al became a football star at Coronado High School, and son Ray served as student body treasurer and ran track. Their life was the very definition of the American Dream—until it shattered in the wake of Pearl Harbor.

As war hysteria and racism surged, Mr. Mayeda—like many community leaders—was swept up by the FBI simply for being a first-generation immigrant and having a role in the local Japanese Association. He had no criminal record, no weapons, no secret affiliations. Yet because he had advocated for cultural unity and had family living in Japan, he became a target. The only "evidence" against Mr. Mayeda included an unsubstantiated report that “someone turned a powerful spotlight onto a high-water tank” during recent blackouts, and that he had once given thirty dollars to a “long-term military relief fund” sent to Japanese relief ministries in Tokyo. Despite thoroughly searching Mr. Mayeda’s home and translating letters written in Japanese, the FBI turned up nothing that could be used against him. An FBI report admitted that the caretaker of the aforementioned water tank advised that “the light was not a powerful spotlight but was apparently from an ordinary flashlight.” The Government also ignored exculpatory evidence, such as the statement from a retired Brigadier General that Mr. Mayeda “is a much better American than most American citizens.”

The long-term consequences for his family were profound. The Mayedas lost their home, livelihood, and precious years they would never recover. Because their son Al enlisted in the U.S. military immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, their son Ray, at age 19, was incarcerated without any family, first held at the Santa Anita horse stables and then the bachelors’ quarters at the Poston War Relocation Center. Mr. Mayeda eventually asked to be repatriated to Japan, where he could be with his second wife and three youngest kids. He knew that this meant separation and possible estrangement from his two eldest sons, but felt he had little choice since he had been imprisoned by the government for years without charge, due solely to his race.

Written by: Daniel Mayeda, grandson of Kunitomo Mayeda

Want to hear about more experiences of others under the AEA? Click a name below to learn more.