Historical Overview

No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Those accused of a crime shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation.

- 5th & 6th Amendments

These protections are guaranteed in the 5th and 6th Amendments to the Constitution of the United States of America.

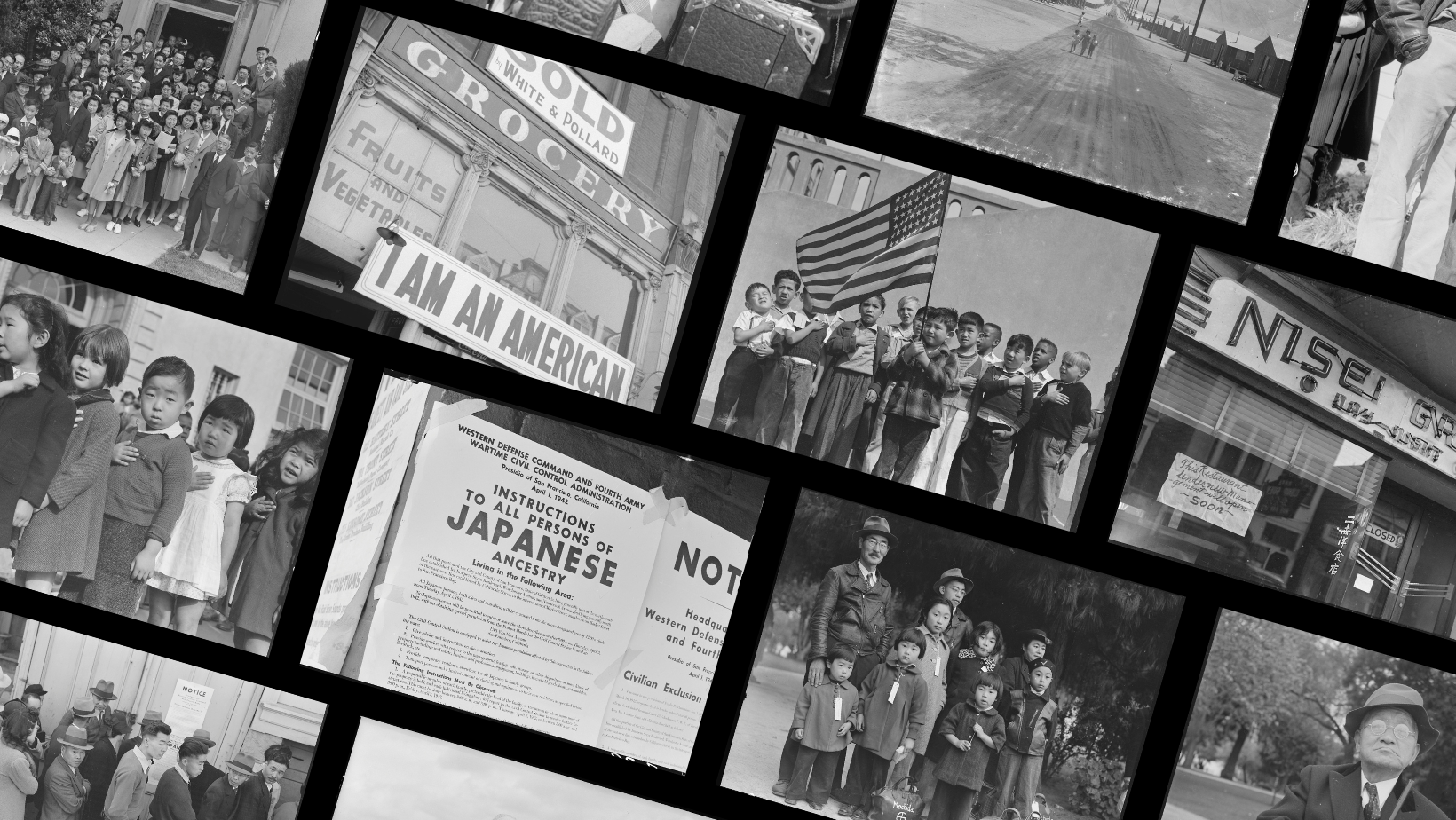

However, during 1942-46, some 120,000 individuals (77,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry and 43,000 Japanese nationals, most of whom were permanent U.S. residents,) were summarily deprived of liberty and property without criminal charges and without trial of any kind. Several persons were also violently deprived of life. All persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast were expelled from their homes and confined in desolate, inland camps, often referred to euphemistically as “internment camps.” The sole basis for these actions was ancestry; citizenship, age, loyalty, and innocence of wrongdoing did not matter. Japanese Americans were the only group singled out for mass incarceration. German and Italian nationals, and American citizens of German and Italian ancestry were not imprisoned en masse even though the U.S. was at war with Germany and Italy.

This episode was one of the worst violations to constitutional liberties that the American people have ever sustained. Many Americans find it difficult to understand how such a massive injustice could have occurred in our democratic nation. This guide will attempt to explain how and why it happened, and what can be done to ameliorate the effects of that mistake. In a 1945 article in the Yale Law Journal, Professor Eugene V. Rostow wrote: “Until the wrong is acknowledged and made right we shall have failed to meet the responsibility of a democratic society—the obligation of equal justice.”

The Mochida Family awaiting “evacuation” in Hayward, CA. May 8, 1942

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

1848

First immigrants from Asia arrived during the California Gold Rush.

Ross Alley, Chinatown, San Francisco, CA - 1890s-1900s

Root Causes

The seeds of prejudice that resulted in the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II were sown nearly a century earlier when the first immigrants from Asia arrived during the California Gold Rush. California was then a lawless frontier. White immigrants from the Eastern United States had just succeeded in taking control of this area from Mexico and had briefly proclaimed an independent Republic of California.

Mexico was forced to cede California to the United States in 1848, and almost simultaneously gold was discovered in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Many migrants from the eastern states, and from all over the world, rushed to California during 1848-49. There was intense, often violent competition for control of the gold mines and ultimately for control of the Republic of California.

Chinese, Gold Mining in California by Roy Graves

About 25 percent of the miners in California during the Gold Rush came from China. The English-speaking newcomers who had previously established dominance over the native, Spanish, and Mexican Californians were in no mood to tolerate further competition. Using acts of terrorism (e.g., mass murder and arson) the white newcomers drove the Chinese out of the mining areas.

When California became a state in 1850, lawless violence against the Chinese was transformed into legal discrimination. Official government prejudice against Asian Americans thus became institutionalized. Article 19 of the California State Constitution authorized cities to totally expel or restrict Chinese persons to segregated areas and prohibited the employment of Chinese persons by public agencies and corporations. Other federal, state, local laws or court decisions at various times prohibited the Chinese from becoming citizens or voting, testifying in court against a white person, engaging in licensed businesses and professions, attending school with whites, and marrying whites. The Chinese alone were required to pay special taxes, and a major source of revenue for many cities, counties and the State of California came from these assessments against the Chinese.

Despite such barriers, there were more opportunities in California than in poverty-stricken China, and more Chinese immigrants arrived. But with the much larger influx of white migrants from the eastern states and Europe, the proportion of Chinese persons in California dropped to 10 percent of the population.

Big business recruited Chinese workers for menial labor, but labor unions agitated for the removal of all Chinese persons from California. Elected officials soon joined the exclusion movement and pressured the federal government to stop immigration from China. In response to this anti-Chinese sentiment, Congress passed a series of Chinese Exclusion Acts beginning in 1882.

“The only one barred out” from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. 1882 - Courtesy of the Library of Congress

1884

The American agricultural industry recruited Japanese laborers to work in the sugar cane fields of Hawaii

Early Japanese immigrants in Hawaii. 1800s

Japanese Arrive

As the Chinese population in California rapidly declined due to the shortage of women and because many men returned to China, an acute labor shortage developed in the Western states and the Protectorate of Hawaii in the 1880s. The agricultural industry wanted another group of laborers who would do menial work at low wages and looked to Japan as a new source. At that time, however, Japan prohibited laborers from leaving the country. The United States pressured Japan to relax the ban on labor emigration, and Japan consequently allowed laborers to leave in 1884.

The American agricultural industry recruited Japanese laborers to work in the sugar cane fields of Hawaii and the fruit and vegetable farms of California. From the handful who were in the U.S. prior to the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Japanese population increased to about 61,000 in Hawaii and 24,000 on the mainland by 1900.

As long as the Japanese remained docile, their hard labor was welcomed, but as soon as they showed signs of initiative, they were perceived as threats to white dominance. Since the major labor unions denied membership to workers of Asian ancestry, the Japanese farm laborers formed independent unions, and together with Mexican farm laborers conducted the first successful agricultural strike in California in 1903. Japanese farm laborers also worked through labor contracting organizations, and their leaders aggressively negotiated for higher pay. They soon achieved wage parity with white workers, and many saved enough money to buy or lease farmland. The Japanese farmers, like their Chinese predecessors, reclaimed much of the less desirable land and developed these into rich agricultural areas.

The anti-Japanese campaign began with acts of violence and lawlessness such as mob assaults and arson. Forcible expulsion from farming areas became commonplace. Soon these prejudices became institutionalized into law. As with the earlier Chinese pioneers, the Japanese were also denied citizenship, prohibited from certain occupations, forced to send their children to segregated schools, and prohibited from marrying whites. In addition, some laws were specifically directed against the Japanese, including the denial of the right to own or lease agricultural land.

Courtesy of The Library of Congress

Like the Chinese exclusion movement before, California lobbied the federal government to stop all immigration from Japan. As a result of these pressures, Japanese laborers were excluded by executive action in 1907, and all Japanese immigration for permanent residence was prohibited by the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924. The Japanese government regarded this as a national insult particularly since the United States had insisted upon Japanese immigration in the first place.

To the dismay of the exclusionists, the Japanese population did not rapidly decrease as the Chinese population did earlier. There were sufficient numbers of Japanese women pioneers who were married, resulting in an American-born generation, and families decided to make the United States their permanent home. As the exclusionists intensified their efforts to get rid of the Japanese, their campaign was enhanced by the development of a powerful new weapon: the mass media.

Newspapers, radio, and motion pictures stereotyped Japanese Americans as untrustworthy and unassimilable. The media did not recognize the fact that a large number of persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were American citizens. As Japan became a military power, the media falsely depicted Japanese Americans as agents for Japan. Newspapers inflamed the “Yellow Peril” myths on the West Coast: radio, movies and comic strips spread the disease of prejudice throughout the United States.

Japanese immigrants arriving at Angel Island immigration station. In the foreground are recent wives of men who returned to Japan to marry them, and picture brides who had yet to meet their husbands. Circa 1915 - Courtesy of the National Archives

Forced into segregated neighborhoods and without access to the media, Japanese Americans were unable to counteract the false stereotypes. Although those born in the United States were culturally American, spoke English fluently, and were well-educated, they faced almost insurmountable discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and social interaction.

1941

A confidential report to the President and the Secretary of State that certified the Japanese Americans possessed an extraordinary degree of loyalty to the United States

The USS Arizona on fire during the attack on Pearl Harbor. 1941 - Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Outbreak of War

Prior to World War II, Germany and Japan became military powers, and in the 1930s began their conquests by annexing neighboring nations by sheer intimidation. Actual military conflicts broke out in Asia when Japan invaded China in 1937, and in Europe when Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

As Germany overran the European continent and drove into Africa and the Soviet Union, and Japan moved into Asia and Southeast Asia, the United States was placed under tremendous pressure to enter the war. In July 1941, the United States, together with Britain and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), imposed a total embargo on exports to Japan, thus effectively cutting off Japanese oil supply.

The United States had broken a Japanese top secret code and was aware of the probability of armed conflict. Consequently, the U.S. government undertook precautionary measures. In October 1941, the State Department dispatched a special investigator, Curtis B. Munson, to check on the disposition of the Japanese American communities on the West Coast and Hawaii.

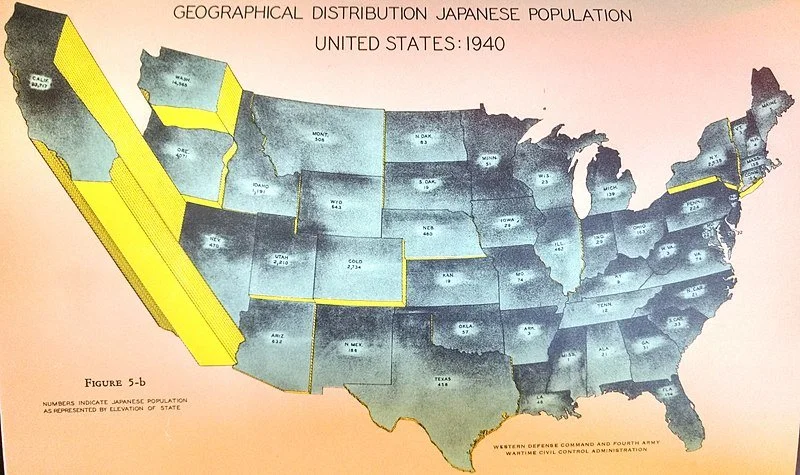

Population of Japanese Americans across the United States as seen in “Final Report Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast 1942” presented by Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt

In October 1941, the State Department dispatched a special investigator, Curtis B. Munson, to check on the disposition of the Japanese American communities on the West Coast and Hawaii.

In November 1941, Munson submitted a confidential report to the President and the Secretary of State which certified that Japanese Americans possessed an extraordinary degree of loyalty to the United States, and immigrant Japanese were of no danger. Munson’s findings were corroborated by years of secret surveillance conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Office of Naval Intelligence. There were a few reports of potential extremists but almost 100 percent of the Japanese American population was said to be absolutely trustworthy. High U.S. government and military officials were aware of these intelligence reports, but they kept them secret from the public. Japan’s military forces attacked the U.S. military bases in Hawaii and the Philippines on December 7, 1941, and the United States declared war on Japan the following day.

Many people who were unfamiliar with the historical background have assumed that the attack on Hawaii was the cause of, or justification for, the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. But that assumption is contradicted by one glaring fact: the Japanese Americans in Hawaii were not similarly incarcerated en masse. Such a massive injustice could not have occurred without the prior history of prejudice and legal discrimination. The removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and their incarceration was the culmination of the movement to eliminate Asians from the West Coast that began nearly 100 years earlier.

The FBI was well prepared for the war, arresting over two thousand persons of Japanese ancestry throughout the United States and the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii within a few days after the declaration of war. Nearly all of those arrested were Japanese nationals, but some American citizens were included.

No charge of espionage, sabotage, or any other crime was ever filed against those arrested. They were apprehended because they were thought to be suspicious persons in the opinion of the FBI. Evidently, anyone who was a community leader was under suspicion by the FBI because almost all of those arrested were organization officers, Buddhist or Shinto priests, newspaper editors, and language or martial-arts school instructors. The established leadership was imprisoned. Inexperienced teenagers and young adults were suddenly thrust into the position of making crucial decisions affecting the entire Japanese American community.

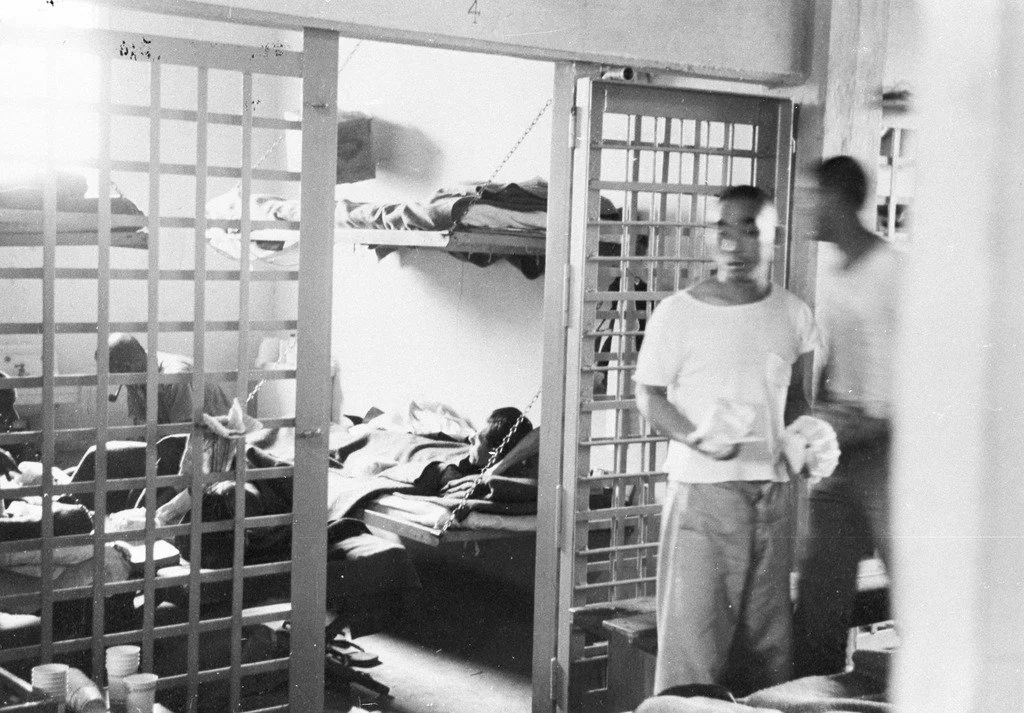

Men were taken away without notice, and their families were left without a means of livelihood. Many also had their bank accounts frozen. Some of those arrested were released after a few weeks, but most were secretly transported to one of twenty-six Department of Justice (DOJ) “internment” or ”isolation” camps scattered in sixteen states and the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii.

Former Tule Lake Incarcerees at the Santa Fe Detention Center. 1946 Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Some families did not learn for years what happened to their men. Most detainees were eventually reunited with their families, but only to be sent to another barbed wire concentration camp where their families had been sent in the meantime. Some, however, were confined in the DOJ camps for the duration of the war, together with the Central and South American Japanese who were brought in for incarceration at the insistence of the United States.

Perhaps due to the swift action of the FBI, there was very little public panic, hysteria, or irrationality for the first month of the war. In fact, public opinion was remarkably enlightened: some newspapers even published editorials and letters sympathetic to Japanese Americans, and some elected officials urged the general public not to blame or harm Japanese Americans.

Economic interests in California, however, were not satisfied with the imprisonment of individuals, and the fact that domestic security was under firm control. They wanted the entire Japanese American population removed from California. The same pressure groups and newspapers that had always advocated Japanese exclusion from the state organized an intense rumor and hate campaign. Totally false stories were published about spies and saboteurs among the Japanese Americans. The war became the perfect pretext for anti-Japanese groups to accomplish the goal they had been seeking for almost fifty years.

The truth was that no person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States or the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii was ever charged with or convicted of espionage or sabotage. Ironically, numerous persons of non-Japanese ancestry were charged and convicted as agents for Japan.

1942

Executive order 9066... used for the purpose of removing and incarcerating Japanese Americans

San Francisco Examiner Headline - April 1942. Courtesy National Archives and Record Administration

Because of the long background of prejudice and stereotypes, many found it easy to believe the false stories. Some high federal officials knew the facts, but they remained silent. By mid-January of 1942, public opinion began to turn against Japanese Americans. Elected officials, city councils, and civic organizations in California, Oregon, and Washington demanded the ouster and incarceration of all Japanese Americans. Earl Warren, then the Attorney General of California, made the incredible statement that the very absence of fifth column activities by Japanese Americans was confirmation that such actions were planned for the future. Warren also claimed American citizens of Japanese ancestry were more dangerous than nationals of Japan. There were a few isolated acts of violence committed against Japanese Americans, but there was no reason to believe that Japanese Americans were in danger despite assertions that the population should be confined for their own safety. If there were any threats, it was the job of local police and sheriff departments to provide protection. Also, many Japanese Americans were perfectly willing to take whatever risk necessary to protect their homes and property.